Hive Minder

...

A week ago, Robb and I put a beehive in the yard of the neighbor who first taught me to spin. She and her partner have a charming garden, and I was delighted to provide them with some bees.

The bees we gave them were the swarm that had landed in our Santa Rosa plum. Prior to moving the bees out of our yard, we did a quick inspection to be certain that the bees looked healthy and spry.

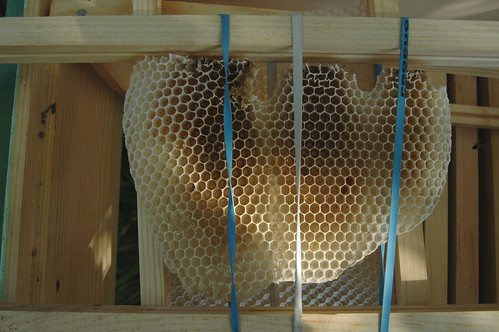

The only problem that we observed was of our own making. We had not filled the entire hive box with frames, and since the bees had open space, they had attached a paddle of comb in the roof of their hive.

We carefully freed this structure, and then rubber-banded it into an empty frame. (I wrote about this technique, just yesterday.) Today, a week later, the bees had already connected the comb to the frame. The girls were hard at work.

They were building lovely fresh comb, and were very relaxed during my inspection. These are wonderfully calm creatures.

Notice the super-fancy catfood cans under the legs of the hive. These can be filled with water, to create an ant-proof moat.

At the time we moved the hive, we added a frame of developing eggs and also capped brood from the Magnolia hive. This way, if anything happened to the Santa Rosa hive's queen, the bees could make another from one of the eggs. I like to offer this bit of insurance to any new colonies.

It was a good thing that I did this, because the bees apparently thought they needed to make a new queen. When I inspected this frame, I saw that the bees had created four emergency queen cells. When the bees are building cells in advance of growing queens, they tend to build on the bottom edges of the comb. In emergency situations, I understand that they build the cells wherever there's a viable larva.

See those peanut-like structures? Those presumably contain queen pupae.

This photograph shows two more queen cells. There's a large closed cup in the upper right area, and also another smaller open cell on the lower left, in which you can see a larval bee. This larva should be receiving special food from the worker bees, which will enable it to develop into a queen bee. Any fertilized bee egg has the potential to become a queen, although only the ones fed on an exclusive diet of so-called royal jelly develop fully functioning reproductive systems.

Unfertilized eggs become the male drone bees, and the queen is capable of choosing if she'll lay fertilized or unfertilized eggs, depending on the needs of the colony.

Once this cell is capped, the bee will pupate. In about eight or nine days, a young queen bee should hatch out. There are a variety of possible ways things could go, if all of the queen cells produce healthy queens. The first to emerge could sting the other queens in their cells, thus eliminating her rivals. The first queen could hatch and any subsequent queens could recruit a following and vamoose before her sister kills her. Or, in some rare cases, they could live together in harmony. And goodness only knows how many more variations are possible, if this colony of bees already has a mature queen...

Only time will tell how this will work out.

Comments

I am greatly encouraged by your efforts and hope to try again one day!

~Traveling Garden Gnome

Do you have the contact details of anyone who can supply you with another mated Queen? I've heard that Queens coming from emergency cells oft times are poor producers.

And I can't believe how yellow your bees are. Mine are nearly all black with just three yellow stripes.

Also, I hate the thought of killing queen bees. It just doesn't seem right.