First Attempts at Fruit Grafting

...

Last weekend was spent in the pre-industrial age. I took a hand spinning class, and collected rabbit manure for my compost. Robb and I bought a French oak barrel with the plan of turning it into a water cistern.

Most excitingly, I went to a Scion Exchange where backyard orchardists and rare fruit enthusiasts shared cuttings of their plants with one another. The idea was that these precious twigs could be grafted onto existing fruit trees, and would in a few years, produce very special fruit.

In the most simplistic terms (the kind I understand!) grafting is a method of asexual propagation, where one type of plant is manually attached to another related plant. A gardener might graft a young stem (scion) onto an existing plant (rootstock) for a variety of reasons. In some cases, the rootstock might be more vigorous than the plant that the scion came from. Or the rootstock might have dwarf characteristics, thus keeping the fruit from growing way up in the air, where it is difficult to harvest. The scion might be added because the fruit on the rootstock needs another variety to function as a pollinator. Or a grower might wish to create a tree that produces multiple varieties of fruit, over an extended growing season. Fruit salad tree, anyone?

Grafting is an ancient technique, and I was pretty excited to try it out. As for the scion exchange itself, I had no idea of what to expect. Did people really give away cuttings of their rare plants, and ask nothing in return?

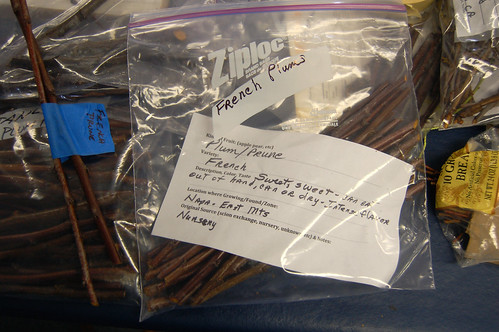

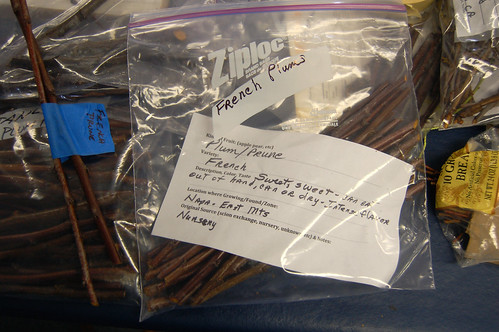

As it turned out, all that was required for participation was a zip-top bag, a waterproof marker, and some tape. Just that, and four bucks entry fee.

Workshops on grafting were being offered, although the huge turn-out made them somewhat chaotic. Thankfully, the always interesting Idell Weydemeyer had excellent class hand-outs.

The place itself was a bit of a madhouse, and none of my photos really captured this. Rows and rows and rows of tables were covered with neatly labeled baggies of stem cuttings. Everything was very well organized, and everyone was very friendly and helpful. (There are some good photos of another scion exchange over at Curbstone Valley's wonderful blog.)

I'm still in awe of the generosity of this event. People want to keep their obscure fruit varieties in production, and so they share, freely.

When I got home, I re-read my notes, watched a few videos online and set to work. My plan was to graft onto the "volunteer" plum tree in our back yard. In retrospect, I wish I had had the good sense to look at the tree before setting out to the exchange. I was a big dummy, and brought home quite a few scions that were just too large to fit onto my twiggy little tree.

I was attempting a style of whip-grafting, in which the tree's branch and the scion are both cut at a diagonal, and their layers of cambion (the green layer of growth, directly under the bark) are in direct contact. This sounds pretty simple, but it was -- not surprisingly -- a bit trickier than I had anticipated. Once lined, up, I taped the twigs together with a paraffin-based medical tape that I got at the event. This should seal out air, and prevent dessication.

I should be able to tell if the grafts "took" in about three weeks. I'm cautiously optimistic.

Since one plum twig looks pretty much like another, Robb created tags, out of cut-up soda cans. We've learned that "sharpie" ink doesn't hold up to the weather around here, so we opted for engraved tags.

Looks a wee bit pathetic, doesn't it?

At the moment, the local citrus trees are in full fruit. This photo shows some of the varieties being grown nearby. Our beautiful old lemon is covered in fruit, as are our two young potted trees. The Meyer lemon is doing very well, and the Murcott mandarin is starting to ripen.

One of the reasons that scion exchanges are so important is that fewer and fewer varieties of fruit are being grown commercially. By sharing rare and older varieties, biodiversity is maintained. This grapefruit was amazingly delicious, but it clearly wouldn't be a big hit at the grocery store. American consumers are apparently more interested in seedless-ness than flavor. So it is up to the rare fruit growers to keep these varieties alive.

I brought home a huge bag of locally grown citrus, including a lemon and an orange whose seeds can produce viable rootstock. I'm going to scoop out the seeds, and see if I can get them to germinate, and then -- who knows? -- maybe I'll use these as rootstock in the future.

I know that many of our blog readers are digging out from the latest snowstorm. Perhaps they can enjoy this little bit of California sunshine, as they dream of spring.

Last weekend was spent in the pre-industrial age. I took a hand spinning class, and collected rabbit manure for my compost. Robb and I bought a French oak barrel with the plan of turning it into a water cistern.

Most excitingly, I went to a Scion Exchange where backyard orchardists and rare fruit enthusiasts shared cuttings of their plants with one another. The idea was that these precious twigs could be grafted onto existing fruit trees, and would in a few years, produce very special fruit.

In the most simplistic terms (the kind I understand!) grafting is a method of asexual propagation, where one type of plant is manually attached to another related plant. A gardener might graft a young stem (scion) onto an existing plant (rootstock) for a variety of reasons. In some cases, the rootstock might be more vigorous than the plant that the scion came from. Or the rootstock might have dwarf characteristics, thus keeping the fruit from growing way up in the air, where it is difficult to harvest. The scion might be added because the fruit on the rootstock needs another variety to function as a pollinator. Or a grower might wish to create a tree that produces multiple varieties of fruit, over an extended growing season. Fruit salad tree, anyone?

Grafting is an ancient technique, and I was pretty excited to try it out. As for the scion exchange itself, I had no idea of what to expect. Did people really give away cuttings of their rare plants, and ask nothing in return?

As it turned out, all that was required for participation was a zip-top bag, a waterproof marker, and some tape. Just that, and four bucks entry fee.

Workshops on grafting were being offered, although the huge turn-out made them somewhat chaotic. Thankfully, the always interesting Idell Weydemeyer had excellent class hand-outs.

The place itself was a bit of a madhouse, and none of my photos really captured this. Rows and rows and rows of tables were covered with neatly labeled baggies of stem cuttings. Everything was very well organized, and everyone was very friendly and helpful. (There are some good photos of another scion exchange over at Curbstone Valley's wonderful blog.)

I'm still in awe of the generosity of this event. People want to keep their obscure fruit varieties in production, and so they share, freely.

When I got home, I re-read my notes, watched a few videos online and set to work. My plan was to graft onto the "volunteer" plum tree in our back yard. In retrospect, I wish I had had the good sense to look at the tree before setting out to the exchange. I was a big dummy, and brought home quite a few scions that were just too large to fit onto my twiggy little tree.

I was attempting a style of whip-grafting, in which the tree's branch and the scion are both cut at a diagonal, and their layers of cambion (the green layer of growth, directly under the bark) are in direct contact. This sounds pretty simple, but it was -- not surprisingly -- a bit trickier than I had anticipated. Once lined, up, I taped the twigs together with a paraffin-based medical tape that I got at the event. This should seal out air, and prevent dessication.

I should be able to tell if the grafts "took" in about three weeks. I'm cautiously optimistic.

Since one plum twig looks pretty much like another, Robb created tags, out of cut-up soda cans. We've learned that "sharpie" ink doesn't hold up to the weather around here, so we opted for engraved tags.

Looks a wee bit pathetic, doesn't it?

At the moment, the local citrus trees are in full fruit. This photo shows some of the varieties being grown nearby. Our beautiful old lemon is covered in fruit, as are our two young potted trees. The Meyer lemon is doing very well, and the Murcott mandarin is starting to ripen.

One of the reasons that scion exchanges are so important is that fewer and fewer varieties of fruit are being grown commercially. By sharing rare and older varieties, biodiversity is maintained. This grapefruit was amazingly delicious, but it clearly wouldn't be a big hit at the grocery store. American consumers are apparently more interested in seedless-ness than flavor. So it is up to the rare fruit growers to keep these varieties alive.

I brought home a huge bag of locally grown citrus, including a lemon and an orange whose seeds can produce viable rootstock. I'm going to scoop out the seeds, and see if I can get them to germinate, and then -- who knows? -- maybe I'll use these as rootstock in the future.

I know that many of our blog readers are digging out from the latest snowstorm. Perhaps they can enjoy this little bit of California sunshine, as they dream of spring.

Comments

But it so exciting to read about your garden and gardening adventures:)